In a related CMA Alert, the Center for Medicare Advocacy discussed the 50 nursing home decisions issued by Administrative Law Judges in 2020, the most recent calendar year when the complete list of decisions is available.[1] At least 39 of the 50 decisions involved deficiencies cited as actual harm or immediate jeopardy. Forty-eight decisions (96%) sustained the deficiencies, which had been cited between 2016 and 2018, and the financial penalties.

The total number of ALJ decisions seems comparatively small. Center for Medicare Advocacy staff wondered how many harm and jeopardy deficiencies had been issued in the three-year period 2016 and 2018 and what proportion of those deficiencies had resulted in ALJ decisions.

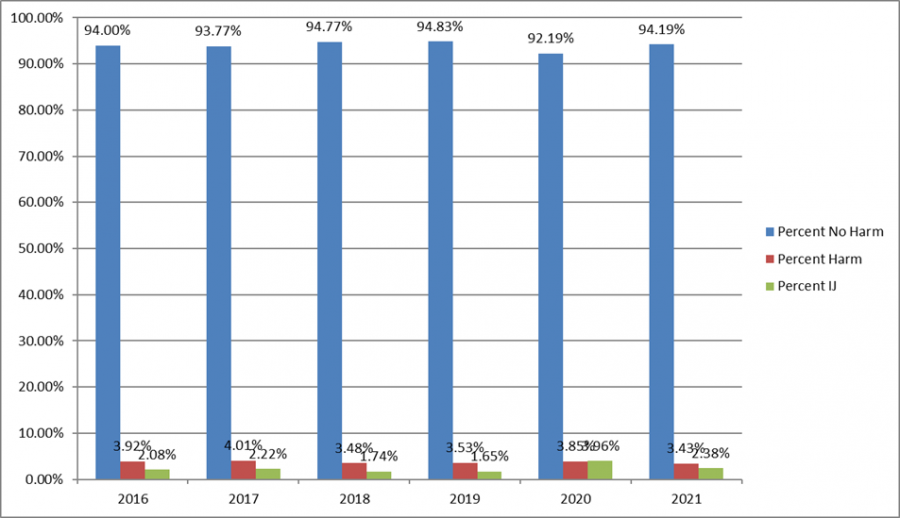

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’s (CMS’s) Quality, Certification and Oversight Reports (QCOR) website shows (as of February 14, 2022) that more than 7,000 surveys resulted in harm and jeopardy deficiencies in 2016 (6% of the deficiencies cited at level D and above), in 2017 (6.23% of the deficiencies cited at level D and above), and in 2018, of fewer than 7,000 surveys (5.22% of the deficiencies cited at level D and above).

Deficiencies, QCOR.cms Data

| Calendar Year | No Harm | Percent No Harm | Harm | Percent Harm | IJ | Percent IJ | Total |

| 2016 | 113311 | 94.00% | 4726 | 3.92% | 2,509 | 2.08% | 120546 |

| 2017 | 111873 | 93.77% | 4783 | 4.01% | 2,653 | 2.22% | 119309 |

| 2018 | 121754 | 94.77% | 4477 | 3.48% | 2,241 | 1.74% | 128472 |

| 2019 | 125299 | 94.83% | 4658 | 3.53% | 2,180 | 1.65% | 132137 |

| 2020 | 61094 | 92.19% | 2551 | 3.85% | 2,624 | 3.96% | 66269 |

| 2021 | 92543 | 94.19% | 3374 | 3.43% | 2,339 | 2.38% | 98256 |

Deficiencies, QCOR.cms Data

As reported, only 50 ALJ decisions about nursing home penalties were issued in 2020. These 50 decisions, reflecting deficiencies cited between 2016 and 2018, are a miniscule percentage of the 21,389 actual harm and immediate jeopardy deficiencies cited in the three-year period – just .002%. Data about how many deficiencies are cited as actual harm or jeopardy demonstrate that the overwhelming majority of actual harm and immediate jeopardy deficiencies are not reflected in decisions issued in the formal appeals system.

Why are there so few ALJ decisions?

At least four answers are possible.

First, CMS may be citing fewer harm and jeopardy deficiencies than in previous years and, consequently, imposing fewer financial penalties. Even if true, however, only .002% of harm and jeopardy deficiencies are addressed in ALJ decisions issued in 2020.

Second, deficiencies may be eliminated or downgraded in the informal dispute resolution process[2] or the independent informal dispute resolution process[2] and are therefore not appealed.

Third, the shift to per instance CMPs as the default type of CMP in 2017[4] may have led facilities to decide it was less costly to pay the penalty than to file an appeal. Moreover, CMPs may be reduced under two sets of circumstances, creating a financial incentive for facilities not to appeal, particularly lower per instance CMPs. First, if a facility waives its right to a hearing, there is an automatic 35% deduction in the penalty amount.[5] Second, if a facility both “self-reports” the noncompliance to the state before it is identified by CMS or the state and promptly corrects the noncompliance, the reduction in the CMP is 50%.[6]

Finally, CMS may be imposing financial penalties but settling facility appeals outside the formal administrative appeals process. The federal regulations authorize CMS to settle CMPS “at any time prior to a final administrative decision.”[7]

While all four reasons are plausible and may be responsible for the limited number of ALJ decisions, the fourth reason seems the most likely basis for the small number of ALJ decisions – settlements are being reached outside the ALJ process.

In “How Nursing Homes’ Worst Offenses Are Hidden From the Public; Thousands of problems identified by state inspectors were never publicly disclosed because of a secretive appeals process, a New York Times investigation found,” The New York Times reports that the appeals process “operates almost entirely in secret” and is “one-sided, excluding patients and their families.”[8] Eighteen States told Times reporters that 37% of citations are removed or downgraded. In Connecticut, for example, “facilities were successful at either erasing or reducing the severity of citations nearly half the time.” The Times also reviewed 76 federal administrative law decisions issued between 2020 and 2021 and found that 10 violations upheld by ALJs were not posted on the federal website. The New York Times’s investigation supports the conclusion that many settlements are occurring outside the appeals process

Limited Public Information about Facility Appeals

At present, there is no way for the general public to know when a facility files an appeal. Although States and the Secretary must make information about survey and certification available to the public within 14 calendar days after the information is made available to facilities,[ix] states are required to send the information about surveys and adverse actions only to the state nursing home ombudsman program.[x] Facility appeals generally become public only if, and when, an ALJ issues a decision.

Moreover, although ALJ decisions record a Docketing Number, the Departmental Appeals Board (DAB) does not make the list of docketed appeals public, at the time appeals are filed or ever. There is no way to compare documented facility appeals with ALJ decisions.

Conclusion

Currently, residents and families have no role in facility appeals (either informal dispute resolution or formal appeals), even when a family complaint is the basis for the complaint survey and deficiency citation. A regulatory change could give residents and their advocates the right to participate directly in facility appeals and present written or oral evidence, or both.

Making docketed appeals public would inform the public of the fact of a facility appeal and enable inquiry and tracking. The Center for Medicare Advocacy has asked the DAB to make the docket of appeals public.

More transparency and accountability are needed in the federal oversight system. More enforcement is needed as well.

February 23, 2022 – T. Edelman

[1] “Nursing Homes Lose Almost All Formal Appeals of Deficiencies and Civil Money Penalties” (CMA Alert, Feb. 24, 2022)

[2] 42 C.F.R. §488.331

[3] 42 C.F.R. §488.331(a)(3)

[4] CMS, “Revision of Civil Money Penalty (CMP) Policies and CMP Analytic Tool,” S&C: 17-37-NH (Jul. 7, 2017); CMS removed this memorandum when it settled National Consumer Voice for Quality Long-Term Care v. Alex M. Azar II, Case No. 21-162 (D.D.C. filed Jan. 18, 2021). See Center for Medicare Advocacy, “Per Day Civil Money Penalties are Back for Nursing Facilities” (CMA Alert, Jul. 29, 2021), https://medicareadvocacy.org/per-day-civil-money-penalties-are-back-for-nursing-facilities/

[5] 42 C.F.R. §488.436(b)(1)

[6] 42 C.F.R. §488.438(c)(2)

[7] 42 C.F.R. §488.444

[8] Robert Gebeloff, Katie Thomas, and Jessica Silver-Greenberg, “How Nursing Homes’ Worst Offenses Are Hidden from the Public,” The New York Times (Dec. 10, 2021), https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/09/business/nursing-home-abuse-inspection.html?searchResultPosition=1