- What Happened to Harm and Jeopardy Deficiencies Cited – and Penalties Imposed – at Nursing Facilities?

- Nursing Homes Lose Almost All Formal Appeals of Deficiencies and Civil Money Penalties

- CT Long-Term Care Ombudsman Program and CMA Launch Innovative Partnership with First Virtual Educational Session

- FREE WEBINAR | Medicare Home Health and DME Update

What Happened to Harm and Jeopardy Deficiencies Cited – and Penalties Imposed – at Nursing Facilities?

In a related CMA Alert, the Center for Medicare Advocacy discussed the 50 nursing home decisions issued by Administrative Law Judges in 2020, the most recent calendar year when the complete list of decisions is available.[1] At least 39 of the 50 decisions involved deficiencies cited as actual harm or immediate jeopardy. Forty-eight decisions (96%) sustained the deficiencies, which had been cited between 2016 and 2018, and the financial penalties.

The total number of ALJ decisions seems comparatively small. Center for Medicare Advocacy staff wondered how many harm and jeopardy deficiencies had been issued in the three-year period 2016 and 2018 and what proportion of those deficiencies had resulted in ALJ decisions.

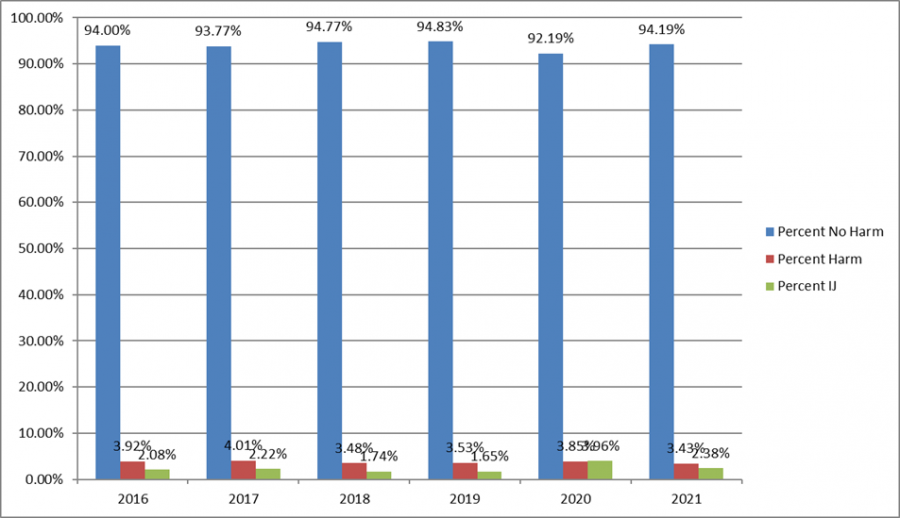

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’s (CMS’s) Quality, Certification and Oversight Reports (QCOR) website shows (as of February 14, 2022) that more than 7,000 surveys resulted in harm and jeopardy deficiencies in 2016 (6% of the deficiencies cited at level D and above), in 2017 (6.23% of the deficiencies cited at level D and above), and in 2018, of fewer than 7,000 surveys (5.22% of the deficiencies cited at level D and above).

Deficiencies, QCOR.cms Data

| Calendar Year | No Harm | Percent No Harm | Harm | Percent Harm | IJ | Percent IJ | Total |

| 2016 | 113311 | 94.00% | 4726 | 3.92% | 2,509 | 2.08% | 120546 |

| 2017 | 111873 | 93.77% | 4783 | 4.01% | 2,653 | 2.22% | 119309 |

| 2018 | 121754 | 94.77% | 4477 | 3.48% | 2,241 | 1.74% | 128472 |

| 2019 | 125299 | 94.83% | 4658 | 3.53% | 2,180 | 1.65% | 132137 |

| 2020 | 61094 | 92.19% | 2551 | 3.85% | 2,624 | 3.96% | 66269 |

| 2021 | 92543 | 94.19% | 3374 | 3.43% | 2,339 | 2.38% | 98256 |

Deficiencies, QCOR.cms Data

As reported, only 50 ALJ decisions about nursing home penalties were issued in 2020. These 50 decisions, reflecting deficiencies cited between 2016 and 2018, are a miniscule percentage of the 21,389 actual harm and immediate jeopardy deficiencies cited in the three-year period – just .002%. Data about how many deficiencies are cited as actual harm or jeopardy demonstrate that the overwhelming majority of actual harm and immediate jeopardy deficiencies are not reflected in decisions issued in the formal appeals system.

Why are there so few ALJ decisions?

At least four answers are possible.

First, CMS may be citing fewer harm and jeopardy deficiencies than in previous years and, consequently, imposing fewer financial penalties. Even if true, however, only .002% of harm and jeopardy deficiencies are addressed in ALJ decisions issued in 2020.

Second, deficiencies may be eliminated or downgraded in the informal dispute resolution process[2] or the independent informal dispute resolution process[2] and are therefore not appealed.

Third, the shift to per instance CMPs as the default type of CMP in 2017[4] may have led facilities to decide it was less costly to pay the penalty than to file an appeal. Moreover, CMPs may be reduced under two sets of circumstances, creating a financial incentive for facilities not to appeal, particularly lower per instance CMPs. First, if a facility waives its right to a hearing, there is an automatic 35% deduction in the penalty amount.[5] Second, if a facility both “self-reports” the noncompliance to the state before it is identified by CMS or the state and promptly corrects the noncompliance, the reduction in the CMP is 50%.[6]

Finally, CMS may be imposing financial penalties but settling facility appeals outside the formal administrative appeals process. The federal regulations authorize CMS to settle CMPS “at any time prior to a final administrative decision.”[7]

While all four reasons are plausible and may be responsible for the limited number of ALJ decisions, the fourth reason seems the most likely basis for the small number of ALJ decisions – settlements are being reached outside the ALJ process.

In “How Nursing Homes’ Worst Offenses Are Hidden From the Public; Thousands of problems identified by state inspectors were never publicly disclosed because of a secretive appeals process, a New York Times investigation found,” The New York Times reports that the appeals process “operates almost entirely in secret” and is “one-sided, excluding patients and their families.”[8] Eighteen States told Times reporters that 37% of citations are removed or downgraded. In Connecticut, for example, “facilities were successful at either erasing or reducing the severity of citations nearly half the time.” The Times also reviewed 76 federal administrative law decisions issued between 2020 and 2021 and found that 10 violations upheld by ALJs were not posted on the federal website. The New York Times’s investigation supports the conclusion that many settlements are occurring outside the appeals process

Limited Public Information about Facility Appeals

At present, there is no way for the general public to know when a facility files an appeal. Although States and the Secretary must make information about survey and certification available to the public within 14 calendar days after the information is made available to facilities,[ix] states are required to send the information about surveys and adverse actions only to the state nursing home ombudsman program.[x] Facility appeals generally become public only if, and when, an ALJ issues a decision.

Moreover, although ALJ decisions record a Docketing Number, the Departmental Appeals Board (DAB) does not make the list of docketed appeals public, at the time appeals are filed or ever. There is no way to compare documented facility appeals with ALJ decisions.

Conclusion

Currently, residents and families have no role in facility appeals (either informal dispute resolution or formal appeals), even when a family complaint is the basis for the complaint survey and deficiency citation. A regulatory change could give residents and their advocates the right to participate directly in facility appeals and present written or oral evidence, or both.

Making docketed appeals public would inform the public of the fact of a facility appeal and enable inquiry and tracking. The Center for Medicare Advocacy has asked the DAB to make the docket of appeals public.

More transparency and accountability are needed in the federal oversight system. More enforcement is needed as well.

___________________

[1] “Nursing Homes Lose Almost All Formal Appeals of Deficiencies and Civil Money Penalties” (CMA Alert, Feb. 24, 2022)

[2] 42 C.F.R. §488.331

[3] 42 C.F.R. §488.331(a)(3)

[4] CMS, “Revision of Civil Money Penalty (CMP) Policies and CMP Analytic Tool,” S&C: 17-37-NH (Jul. 7, 2017); CMS removed this memorandum when it settled National Consumer Voice for Quality Long-Term Care v. Alex M. Azar II, Case No. 21-162 (D.D.C. filed Jan. 18, 2021). See Center for Medicare Advocacy, “Per Day Civil Money Penalties are Back for Nursing Facilities” (CMA Alert, Jul. 29, 2021), https://medicareadvocacy.org/per-day-civil-money-penalties-are-back-for-nursing-facilities/

[5] 42 C.F.R. §488.436(b)(1)

[6] 42 C.F.R. §488.438(c)(2)

[7] 42 C.F.R. §488.444

[8] Robert Gebeloff, Katie Thomas, and Jessica Silver-Greenberg, “How Nursing Homes’ Worst Offenses Are Hidden from the Public,” The New York Times (Dec. 10, 2021), https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/09/business/nursing-home-abuse-inspection.html?searchResultPosition=1

– top –

As Black History Month Ends, Continue Questioning.Structural Racism in Health Care Workforce: A study published in Health Affairs found that Black women are “more overrepresented in health care and more concentrated in the lowest-wage direct care jobs” than any other racial or ethnic group of women and of all men.[1] An analysis of American Community Survey[2] data from 2019 revealed that almost 23% of Black women in the workforce are employed in the health care sector, with a majority (64.7%) working as licensed practical nurses or nurse aides, and 40% working in long-term care.The authors of the study contend that structural racism in the nation’s labor market created this stratification. Furthermore, the study argues, the intersection of gender and race advanced a culturally constructed division of care. According to the authors, Black women and women of color have historically, through a legacy of slavery, been relegated to more physically demanding direct care work, along with jobs that were more strenuous and were thought to require “little or no skill.” Carried over to today’s workforce, direct care workers “face difficult and dangerous working conditions.” With heath care workers having the “highest rates of workplace injuries of any industry in the United States.”Policy considerations proposed by the authors to combat and improve racial equity include:

The authors conclude that “investing in Black women through targeted investment in care infrastructure could begin to undermine some of the ideological constructions and structural barriers” that have devalued both Black women and care work.___________________[1] Dill, J., & Duffy, M. Structural Racism and Black Women’s Employment In The US Health Care Sector. Health Affairs. (February 2022). Available at: https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/10.1377/hlthaff.2021.01400 |

Nursing Homes Lose Almost All Formal Appeals of Deficiencies and Civil Money Penalties

The Nursing Home Reform Law authorizes nursing facilities to appeal deficiencies that are cited against them for noncompliance with federal standards of care if the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) imposes a financial penalty for the deficiencies.[1] CMS generally focuses financial penalties on facilities whose deficiencies are said to cause actual harm or immediate jeopardy to residents, the top two levels of harm out of four levels. As shown below, CMS wins most administrative appeals – 96% – that are officially released. However, as reported today in a companion Alert, it appears that many other harm and jeopardy deficiencies and their penalties are being resolved outside the formal appeals process, without any public information about the resolution of these deficiencies and penalties. More transparency about the nursing home oversight system is plainly needed.

Administrative Law Judge hearings

The Center for Medicare Advocacy analyzed the 53 decisions of Departmental Appeals Board’s Administrative Law Judges (ALJs) issued in 2020, the most recent year with complete data, that reviewed nursing facilities’ appeals.

Fifty of 53 nursing home decisions address nursing home deficiencies and remedies (two decisions dismissed facility appeals when no remedies were imposed; a third decision confirmed the effective date of a facility’s participation in Medicare.) Analysis of the 50 decisions finds:

- ALJs upheld deficiencies and civil money penalties (CMPs) in 48 decisions (96%); ALJs ruled for the facility in two decisions (4%)

- Immediate jeopardy deficiencies were cited in 29 decisions, harm, in 10 decisions. (In cases where CMS imposed per instance CMPs, ALJs do not necessarily identify whether deficiencies are classified as harm or jeopardy.)

- The most common deficiencies addressed in ALJ decisions: accident prevention/supervision (21 decisions), abuse (8 decisions), and pressure sores (6 decisions)

- California had the most decisions (12), following by Texas (10); 20 other states had one to four decisions each

- Appeals were decided by summary judgment (20 decisions); by the written record or the parties’ written exchanges (18 decisions); by a hearing (12 decisions)

- Per day civil money penalties (CMPs) were imposed in 27 cases (ranging from $18,164 to $1,449,975 and averaging $211,585), per instance CMPs in 23 cases (ranging from $7,550 to $20,964 and averaging $14,298)

- Deficiencies were most commonly cited as a result of surveys conducted in 2017: 20 decisions; in surveys conducted in 2016 and 2018: 10 decisions each

What the Data Show

CMS wins most of the appeals, with ALJs sustaining the deficiencies and CMPs. Occasionally, an ALJ rejects one of multiple deficiencies cited or reduces the duration of a per day CMP, but almost always, ALJs sustain deficiencies and CMPs in their entirety.

The deficiencies appealed by facilities are significant and reflect serious failures in care resulting in resident harm. They are most frequently related to facilities’ failure provide adequate supervision to residents – an obvious staffing issue.

Despite CMS’s guidance that CMPs “should at least exceed the amount saved by the facility by not maintaining compliance,”[2] CMPs, especially per instance CMPs, are small in amount. The Trump Administration’s survey guidance in July 2017 that shifted the default penalty from per day to per instance[3] led to a greater proportion of per instance CMPs.

Facility appeals are most often decided by summary judgment or by review of written filings and exchanges. Decisions are largely based on facility records. In only a minority of cases are factual disputes at issue that require evidentiary hearings.

Appeals are typically not decided until three years after the deficiencies are first cited. Facilities are not required to pay CMPs until after appeals.[4]

The following two decisions show serious deficiencies, reflect decisions by summary judgment, illustrate that per day CMPs are considerably higher than per instance CMPs, and show a lengthy delay between the citing of the deficiency and the ALJ decision:

In a summary judgment decision in Golden Acres Living and Rehabilitation Center v. CMS,[5] ALJ Leslie C. Rogall sustained a harm-level supervision deficiency and a per day CMP totaling $81,065 for failing to supervise a resident while she was toileting and ambulating, despite facility assessments identifying the resident’s risk for falls and care plans requiring that staff supervise her. The resident had numerous unwitnessed falls at the facility while not supervised and may have fractured two ribs from an unsupervised fall. The survey was completed April 13, 2017; the ALJ decision is dated November 23, 2020.

In a summary judgment decision in Logan Healthcare Leasing, LLC d/b/a Logan Care and Rehabilitation,[6] ALJ Leslie A. Weyn sustained an immediate jeopardy supervision deficiency and a per instance CMP of $20,905 for failure to follow its smoking policy and to supervise a resident directly when he was smoking. The resident burned himself smoking in his room and was hospitalized with a second degree burn on his neck. The deficiency was cited in a complaint survey completed January 30, 2018; the ALJ decision is dated August 5, 2020.

___________________

[1] 42 U.S.C. §§1395i-3(h), 1396r(h), Medicare and Medicaid, respectively; 42 C.F.R. §488.408(g)(1) (“A facility may appeal a certification of noncompliance leading to an enforcement remedy.”)

[2] State Operations Manual, Chapter 7, §7400.4

[3] CMS, “Revision of Civil Money Penalty (CMP) Policies and CMP Analytic Tool,” S&C: 17-37-NH (Jul. 7, 2017); CMS removed this memorandum when it settled National Consumer Voice for Quality Long-Term Care v. Alex M. Azar II, Case No. 21-162 (D.D.C. filed Jan. 18, 2021). See Center for Medicare Advocacy, “Per Day Civil Money Penalties are Back for Nursing Facilities” (CMA Alert, Jul. 29, 2021), https://medicareadvocacy.org/per-day-civil-money-penalties-are-back-for-nursing-facilities/

[4] 42 C.F.R. §§488.440(b). 488.442(a)(1)-(3)

[5] Docket No. C-17-1109, Decision No. CR5767 (Nov. 23, 2020), https://www.hhs.gov/about/agencies/dab/decisions/alj-decisions/2020/alj-cr5767/index.html

[6] Docket No. C-19-8, Decision No. CR5677 (Aug. 5, 2020), https://www.hhs.gov/about/agencies/dab/decisions/alj-decisions/2020/alj-cr5677/index.html

– top –

CT Long-Term Care Ombudsman Program and CMA Launch Innovative Partnership with First Virtual Educational Session

Connecticut nursing home residents, family members, and caregivers attended the first virtual education session held as a collaborative effort between the Center for Medicare Advocacy and the CT Long-Term Care Ombudsman Program this week. The goal of this educational series, supported by a grant from Point32Health and the CT Department of Aging and Disability Services, is to benefit the state’s long-term care residents and families by increasing health literacy, enhancing age-friendly health care, and improving outcomes for nursing home residents. In this first educational session, CMA and the CT Long-Term Care Ombudsman Program provided an overview of the services that each organization provides and shared relevant key insights about residents’ rights and Medicare benefits.

CT Long-Term Care Ombudsman Mairead Painter started off the session by providing information on the state’s Long-Term Care Ombudsman Program, which advocates for and protects the health, safety, welfare, and rights of long-term care residents. The Ombuds program also responds to and investigates complaints brought by residents, family members, and other concerned parties. Initiatives prioritized by the Ombuds program include a platform of inclusivity in long-term care facilities, which includes the development of an Inclusive Communities work group that focuses on education and outreach to support people who identify as members of multiple marginalized groups, including the LGBT community.

From there, the Center’s Executive Director, Judith Stein and Associate Director, Kathleen Holt provided detailed information about Medicare nursing home coverage, including coverage criteria, the Medicare “benefit period,” coverage of maintenance therapy and skilled nursing care, along with information and a resource guide about Medicare Savings Programs. Ms. Stein and Ms. Holt also answered questions from attendees about Medicare Advantage versus traditional Medicare and Medigap plans.

The session was recorded and will be available on the website of the Center for Medicare Advocacy and on the Long-Term Care Ombudsman Program YouTube page.

– top –

FREE WEBINAR | Medicare Home Health and DME Update

Thursday, April 28, 2022 @ 1 – 2:30 PM EST

Sponsored by California Health Advocates

Presented by Center for Medicare Advocacy Executive Director, attorney Judith Stein, and Associate Director, attorney Kathleen Holt, the presentation includes a 30-minute live question & answer session.

Register Now:https://attendee.gotowebinar.com/register/1457421769888387854

– top –